Despite ongoing conflict and economic meltdown, Bukovel is probably the world’s fastest growing winter sports resort.

The conflict may be grinding on in eastern Ukraine but on the slopes of Bukovel, skiers’ main concern is the state of Carpathian snow. It has been an unusually mild winter and yet, despite the snow conditions — and despite the fighting in Donbass and, for that matter, Ukraine’s economic meltdown — the ski resort is about to celebrate the end of another highly successful season. When I visited late last month, there was hardly a bed to be had.

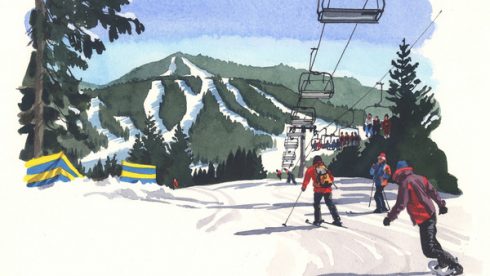

In the west of Ukraine, about 160km south of Lviv, Bukovel is set between five mountains thickly clad with conifers. It claims to be the biggest ski area in eastern Europe, and is probably the world’s fastest growing winter sports resort — it has attracted 1.55m visitors so far this season, up from 206,000 in the winter of 2005-06. There are 60km of pistes and 16 lifts, as well as snow biking, dog sleigh rides, snow rafting and an array of summer activities such as the Extreme Park, where you swing Tarzan-like between the tall trees.

My arrival coincided with one of Ukraine’s less well known diversions, Iz Zhinkoyu Na Shyyi (“With a Woman on the Neck”), in which husbands carried their wives across their shoulders over a televised obstacle course to Benny Hill-style background music. They leapt a gate, picked a flower from a snow drift, stepped through an icy puddle covered in eggs, stamped out an inflated balloon, then delivered their beloved cargo across the finish line as the crowds applauded.

Such high jinks might be a welcome distraction after the national traumas of the past two years. Since the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovich in February 2014, Russia’s ensuing annexation of Crimea and its stoking of a war in Donbass that has killed at least 9,000, normality still seems a long way off. Meanwhile the economy struggles, and the hryvnia flounders at 30 per cent of its former value. Yet even as their country tumbled towards full-scale war with its neighbour in the winter of 2013-14, Ukrainians skied in droves. “Politics are unimportant here — skiing is a style of life,” one bar owner told me, proferring a bracing tot of Jägermeister from a flask hidden in one of his ski poles. True, but only to a point: Russian skiers, who formed a third of visitors before 2014, are now notable by their absence.

The purpose-built resort opened in 2002 and was then developed further with the help of Ecosign, the Canadian mountain resort planner also responsible for Whistler and Krasnaya Polyana in Russia.

“There was nothing here,” said Oleksandr Shevchenko, 44, co-founder and general manager of Bukovel, “no houses, no roads, no power lines, no structures. We built it all.”

He had come up with the plan after making his first ski trip, to Slovakia, in 1999 and realising Ukraine lacked a major resort. An investment of $600m came from Ihor Kolomoisky, one of the country’s richest men, whose Privat Group owns Ukraine’s largest bank, two airlines and a host of television channels.

The project is not without its critics, however. These valleys were once studded with the farmsteads and villages of the Hutsul people, known for their striking wooden architecture, traditional clothing and strong tasting cheese (bryndza). Some worry about the impact of Shevchenko’s ambition to almost double the amount of pistes, to 116km.

During my visit, it did feel at times as if Hutsul culture was being replaced by an imitation: the stalls of packaged Hutsul crafts, for example, the folksy architecture of the new buildings and the surprise appearance at the top of a slope of a “Hutsul” man in traditional garb offering to blow his long wooden horn (trembita) for a fee. Any protest has been muted, however. The work opportunities are welcome, and the price of land has risen tenfold, making some homesteaders very rich.

“We had two revolutions, a global economic crisis, a war with Russia, a corruption problem, and even so the resort has developed,” Shevchenko told me. He batted away any suggestion that the fighting in the east of the country might scare people off. “Visitor numbers have been increasing every year, and we are always developing, always open for business and investment. We’ll take any money that’s good — except Putin’s of course,” he said with a smile.