Canadian Paul Mathews is the world’s pre-eminent ski resort designer, having created more than 400 of them around the world. He explains the principles behind a perfect trip to the snow.

Canadian Paul Mathews is the world’s pre-eminent ski resort designer, having created more than 400 of them around the world. He explains the principles behind a perfect trip to the snow.

So the story goes, Russia’s Winter Olympics site started with Canadian Paul Mathews in a private jet overlooking the Western Caucasus in 2000. After two hours he’d seen nothing, much to his host’s frustration. But then, from 15,000 feet in the air, he caught site of a small access road, a river, a gentle plateau, steep hills and bowls. “Whoa, whoa, whoa!” he said. “Turn this plane around!”

Until Mathews saw it, the Rosa Khutor Alpine Ski Resort wasn’t a ski resort at all, just an empty stretch of mountain. After Mathews saw it, $165 million (NOK1bn) was spent turning “Rosa’s Hut” into a ski resort that became the alpine centre for the Sochi Olympics, and briefly the focal point for the world.

You may not have heard of Mathews, but he might just be the most influential person in the world of skiing. Since starting his Ecosign firm in 1975, and making the fledgling resort of Whistler in British Columbia his first project, he has designed more than 400 resorts in 39 countries and helped create five Winter Olympic alpine resorts. If you’re one of the roughly 115 million regular skiers around the world, it’s almost certain that you’ve skied on a resort conceived at least in part by Mathews and his firm. His gift, he has said, “is seeing things that other people can’t see… and not being afraid to tell the truth, even when it’s not what my clients want to hear”.

Ecosign’s work stretches from Trysil and Hemsedal in Norway to Zermatt, Laax and Courchevel in the Alps, Niseko in Japan and many of the new resorts in developing countries in Asia and Eastern Europe. They’ve helped bring skiing to Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Turkmenistan.

Doing masterplans for both resorts and ski areas, they might rejig a lift network, as in Courchevel; redesign the structure of the town, as in Trysil; or create an entire resort from scratch, as with Rosa Khutor or more recently Changbaishan in China.

“We do it all,” says Mathews over the phone from Canada on a Sunday morning. He spends half the year travelling, and can often be found in helicopters (“I’ve recently been flying round Serbia in military helicopters,” he says). He’s just back from Tokyo, and is about to head to Switzerland where he’ll meet the Beijing bid committee for the 2022 Olympics and show the International Ski Federation (FIS) his latest masterplan, for the Jungfrau-Grindelwald ski areas. He’s straight-talking, chipper and happy to share his encyclopaedic knowledge of resorts around the world, even if we’re stopping him eating his breakfast.

While Ecosign is the leader in a niche industry, Mathews insists “we’re still a boutique firm. There are only 25 of us, and it’s still very personal to us – we see ski resorts in our sleep. Giant architecture firms like Aecom [the world’s largest, with 1,370 architects] have tried doing ski resort design, but frankly they’re lousy at it.”

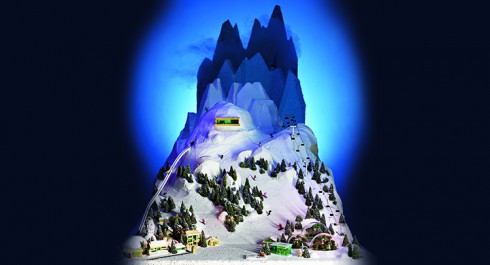

What they have done from the start is create resorts that work on a “human scale”, which is something of a mantra. “To us, a classic ski resort is a place that’s nice to stay at – where you can ski in and ski out; where there’s little or no traffic; where you can get great food easily; which is in keeping with the environment. I can’t stand those purpose-built French ski factories – it feels like man dominating nature, and you don’t leave the city to be trapped in a monstrous high-rise.” A typical Ecosign resort has underground parking, a village feel, accommodation right on the slopes, and none of his pet peeve – steep, icy, exterior staircases.

A keen skier and self-confessed tree-hugger, Mathews studied forest ecology and landscape architecture at the University of Washington in the early 1970s. After spending a winter in Zermatt, Switzerland, he was impressed by being in a resort with no cars, and became fixated on the environmental insensitivity of many American ski resorts. “You’d see bulldozers and power lines, and every family needed three car parking spaces for their trip. There was a brutality and an environmental insensitivity about a lot of the design, or the lack of it.”

He was soon drawn to the fledgling resort of Whistler, north of the border near Vancouver, admitting, “I just loved the place, the powder, the beer and the Canadian girls, not necessarily in that order.” Still, Whistler back then was very different to the way it is today. Lifts and runs had been designed by ski instructors on summertime hikes, cars ruled and there was little in the way of ecological awareness in the layout of the pistes.

His first job, in 1975, was working on a parking and skier staging analysis for Franz Wilhelmsen, the man behind Whistler’s launch as a ski resort in 1966. After further commissions for Hemlock Valley Resort and Mount Washington in British Columbia, by 1978 he was back at Whistler to create a masterplan for the ski area alongside landscape architect Eldon Beck, who designed the new Whistler Village. Their vision was of a pedestrian-centred space, inspired by Swiss mountain villages, which emphasised community and sensitivity to the mountains. It was a pioneering concept which has not only won countless awards but planted the idea that a ski resort can be seen as a single holistic vision, from the slopes to the car parks and even the slopeside Jacuzzis.

Behind a lot of the plan was the environment. The pistes Ecosign planned moved with the natural terrain, and straw and seed were planted on the ground to prevent erosion. Mathews hired biologists to inventory the mountain’s flora and fauna, and planted trees that mimicked the glading found in nature. He claims to have improved Whistler’s ecological integrity tenfold. “It was,” he says simply, “about respect for the mountain, and not being a knucklehead. With Whistler, we proved that you can create a big resort sensitively.”

That led to more commissions in British Columbia, then Idaho and Washington, before Ecosign latched onto the Japanese ski resort boom, when the country saw nearly 500 resorts in the mid-’80s swell to around 700 by the mid-’90s. By 1989, Mathews had broken Europe with a masterplan for Laax, Switzerland, which involved a few classic pieces of Ecosign resort planning: creating a pedestrian-orientated central village, and merging ski operators to improve efficiency.

While the environment is at the centre of a lot of what Ecosign does, it’s also about common sense. When he had a brief to redesign Hemsedal in Norway in 1995, he noticed that “monster traffic jams” formed as people drove to the 10,000 tourist beds in farmhouses scattered around the region. “The ski centre was perched on the side of the mountain. It was all very precarious, so we recommended they build the village at the bottom of the mountain, with centralised parking and new units on the piste.” The traffic problems virtually disappeared, and the yearly number of skiers has almost doubled, from around 350,000 to around 680,000.

In Trysil, the largest ski resort in Norway, he told them to get rid of the T-bars and bring in six-seater chair lifts, and to build a large car park at the bottom of the resort, with a new resort village on the former parking lots. This turned the area around the bottom of the pistes into a ski-in/ski-out area. Since 1996, skier numbers have gone from 400,000 to 800,000.

There’s still plenty of work being done on ski resorts in Europe, including the development of Andermatt (see sidebar), but Mathews says: “For the most part, the European Alps and North America are saturated – there aren’t enough skiers to expand much. I’m looking at a lot of resort development in the Balkans – they’re looking at seven potential resorts in Montenegro – and the new frontiers of Russia, India and China.”

Ecosign is already doing the planning for the freestyle skiing and snowboarding venues for the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeonchang, South Korea, and is currently consulting with Beijing over a bid for the 2022 Games (Oslo and Stockholm pulled out of the race, leaving just Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan). In the past, Ecosign has worked on Winter Olympics at Calgary in 1988, Salt Lake City in 2002 and Whistler in 2010, as well as Sochi.

So how does the process of creating a masterplan work? It usually starts with satellite images to map areas, calculating solar radiation levels and finding areas with just the right amount of slope to provide good snow conditions. New software originally developed for the forestry industry can calculate exactly where the best snow will be and where the sun will be strongest.

The usable slopes are colour-coded – flat runs are white, beginner runs are green, intermediate yellow and expert blue, while slopes which are too steep are marked red. Foresters and surveyors then head up the mountains on snowmobiles or in helicopters, armed with GPS to work out exactly where the pistes will be and where trees need to be removed. Once that’s done, the team will place transparent onionskin paper over the maps and draw plans in pencil, the same way they have since Ecosign started in the ’70s.

It’s a process that can take up to six months, while actually creating the pistes can take years.

According to Mathews, “The technology has improved, and we’ve improved, but at its core the design process has stayed the same.” Still, ski resorts have changed, and almost entirely for the better according to Mathews. Lifts are three times faster than they were in the 1970s, and the snow cannons more effective, meaning that that skiers can go much further in a day, on more reliable snow.

The joining of ski areas to create mega-areas – as at France’s Les Trois Vallées, with 493km of pistes – is, he says, “good for everyone. It’s great news for skiers and for the environment, because you don’t need a car anymore to find new places to ski.” Today, Ecosign is working to reduce the number of cars going to ski resorts, full stop. Mathews is proud, for example, that 70 per cent of international visitors to Whistler no longer rent a car. The aim of most Ecosign resorts now is to have fewer than one car for every two tourist residences.

“Ultimately,” says Mathews, “it comes down to making a place you want to spend time in. The most satisfying thing for me is getting a pair of skis on and skiing the pistes like everyone else. That’s really what it’s all about.”