Whistler Olympic Park designer Paul Mathews has helped craft 320 ski areas in 34 countries, including Switzerland, where being a ski bum inspired his life’s work.

Whistler Olympic Park designer Paul Mathews has helped craft 320 ski areas in 34 countries, including Switzerland, where being a ski bum inspired his life’s work.

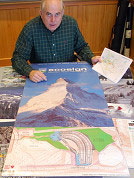

The 62-year-old American-Canadian is the founder of Ecosign, an environmentally friendly planning firm commissioned to create the Olympic Nordic centre and ski jumps where Swiss Simon Ammann could be a favourite to win.

But even recreational skiers should know Mathews’ work well. His firm has left its mark on more than a dozen high-profile winter resorts in Switzerland, from streamlining services in Zermatt to a complete overhaul in Andermatt. Each one of his projects carries elements he first picked up in the Alps.

“My whole career has been based on things I saw in Switzerland during my ski bum days in Zermatt,” he says in his Whistler office lined with dossiers on places he has worked – Japan, Kazakhstan, Russia, South America, China, Norway, the United States and, of course, Canada, among scores of others.

“I love the way developments in Switzerland are very compact and pedestrian friendly. The Swiss handle the landscape with a higher level of professionalism and environmentalism than almost any country in the world. The whole country looks like a national park.”

Virgin territory

Ecosign was the lead firm behind the design of the brand new Whistler Olympic Park, a sprawling network of nearly 100km of cross country ski trails that wind under droopy spruce and past two spectacular ski jumps.

The 115 million Canadian dollar (SFr113.67 million) facility is designed so spectators will be able to see far more of the cross country and ski jumping action than at other, similar Olympic venues.

“Normally you go to a cross country race and you see everyone line up and take off, but then you go to the bar for an hour and wait for them to come back,” Mathews said. “Here you can see the skiers race on the ups and downs. I’d say you can see 40 to 50 per cent of the action.”

Located in the Callaghan Valley about 20km west of Whistler, the park also includes a shooting range for biathlon events and offers plenty of room for temporary tents to house media, officials and ski technicians. When the Games are gone, much of the parking and transport areas will be torn down and converted back into forest.

“In Switzerland the paperwork you have to do to cut down a single tree is about the same as what you have to do for a whole forest in British Columbia,” Mathews said. “The site for the Olympic park was pure virgin territory. There was nothing there. We personally went out and flagged all the trees that we wanted to save.”

In doing so, Mathews says he was able to reduce the park’s footprint by more than a third compared with other proposals.

British Columbia, Switzerland

Mathews founded Ecosign in 1975, a few years after he’d spent a winter living in Zermatt and skiing as much as he could. The experience left an indelible impression on him. Today his promotional materials use close-up shots of the Matterhorn.

Mathews founded Ecosign in 1975, a few years after he’d spent a winter living in Zermatt and skiing as much as he could. The experience left an indelible impression on him. Today his promotional materials use close-up shots of the Matterhorn.

“I was so astonished when I left the valley,” he said. “With no cars in Zermatt, I hadn’t smelled the internal combustion engine for months. It hit me like a brick that our air is pretty polluted so I wanted to bring that principle of human-friendly, medium density building to ski areas elsewhere.”

The effort has paid off enormously. This is the third time Mathew’s firm has worked on an Olympic venue. It will soon be four. He recently flew around Sochi, Russia, in a helicopter with Prime Minister Vladimir Putin to scope out design ideas for the 2014 Winter Games.

In October 2009, Mathews also won a contract with operators in the Jungfrau region to find ways of streamlining services, lifts and transport between areas like Grindelwald and Wengen to create a seamless recreational region.

It’s a job he’s looking forward to, especially since it brings him back so close to where it all began. But for now Mathews gazes out his office windows at the snow piling up. You could forgive him for thinking, at least for a moment, he’s somewhere deep in the Alps.

“British Columbia is Switzerland without the people,” he said. “I’ve learned a lot from the Swiss.”